In October, Aimee Wall boarded a plane to spend three weeks at the Tyrone Guthrie Centre in Annaghmakerrig, Ireland, as the 2024 Max Margles Writer in Residence. Here is first of her two dispatches. Read Part Two.

The strangest and most luxurious thing about being here is that there actually are enough hours in the day. It took me a little while to realize it, to not feel rushed or possessive of my time, to know that it’s okay to get caught up in an interesting conversation with other residents at the breakfast table, linger a little longer than anticipated, because the rest of the day still stretches out ahead of me and all I have to do is write and think and show up for dinner at seven, and there is so much to learn from the others here that I’m loath to stick to a strict schedule. There is more than enough time for all of it, and this is the real gift.

As I write this, I’ve been here at the Tyrone Guthrie Centre at Annaghmakerrig for nearly two weeks. A rhythm has been established. I wake up and open the big wooden shutters on the windows in my room, which looks out the front of the “Big House” onto the lake. Downstairs for coffee, and then back up to my desk. At ten o’clock, a rotating cast of characters convene downstairs again for a cold dip in the lake—I was thrilled to get here and find myself among so many people game for daily frigid swims. I got hooked, haven’t yet missed a day. And then I spend the rest of my day at my desk, writing and reading and thinking, spreading my notes out over the carpet, before taking a walk in the forest or along the narrow roads.

Every night at seven, we all gather for dinner downstairs. When Tyrone Guthrie left his ancestral home, Annaghmakerrig House, to the Irish state for the use of artists and “other like persons,” it came with one stipulation—that the guests of the Big House meet for dinner every night at seven o’clock—and this rule, one of the few, and a good one, has remained in place in all the years the residency has existed.

We eat in what would have been the original kitchen of the house. The back kitchen, a working kitchen. The people who lived here would likely have eaten in a dining room somewhere in the front. I’m happy we’re in the kitchen, where a long wooden table sits in front of the original hearth, which now hosts a woodstove and so, sometimes, a fire, on the chillier nights. We are generally eleven or twelve at the table, and the dinners are gorgeous and hearty. Some nights it’s quiet, our heads still full of our work from the day, we eat an unfailingly beautiful meal and chat with our neighbours and head up to bed. Other nights, an accordion comes out, or a fiddle, and then people are sharing poems, or songs, or we just hang out talking and telling stories and drinking wine and tea. There is a beautiful sitting room in the front that we’re free to use, but we always stay in the warm kitchen, the hearth of the house. I feel lucky to have found myself here among all these poets and musicians and painters who have come here with purpose, but also such openness, and generosity. One night, we dance in the kitchen; on another, we take an impromptu tour of the studios.

I came here to work on a novel. It’s early days yet, I am still feeling my way through the bones of it, the initial structure, the little world of it. I am trying, in part, to write about an apartment, about the strange tension and precarity of making homes in rented spaces, and about the physical marks and traces we leave on the places we live in, what they bear of our presence after we leave. Here, I sit down to do this writing and thinking every day at a big old wooden desk covered in scarred burgundy leather, in my room in this house that has had so many lives, seen so many people pass through its halls and sit at its table.

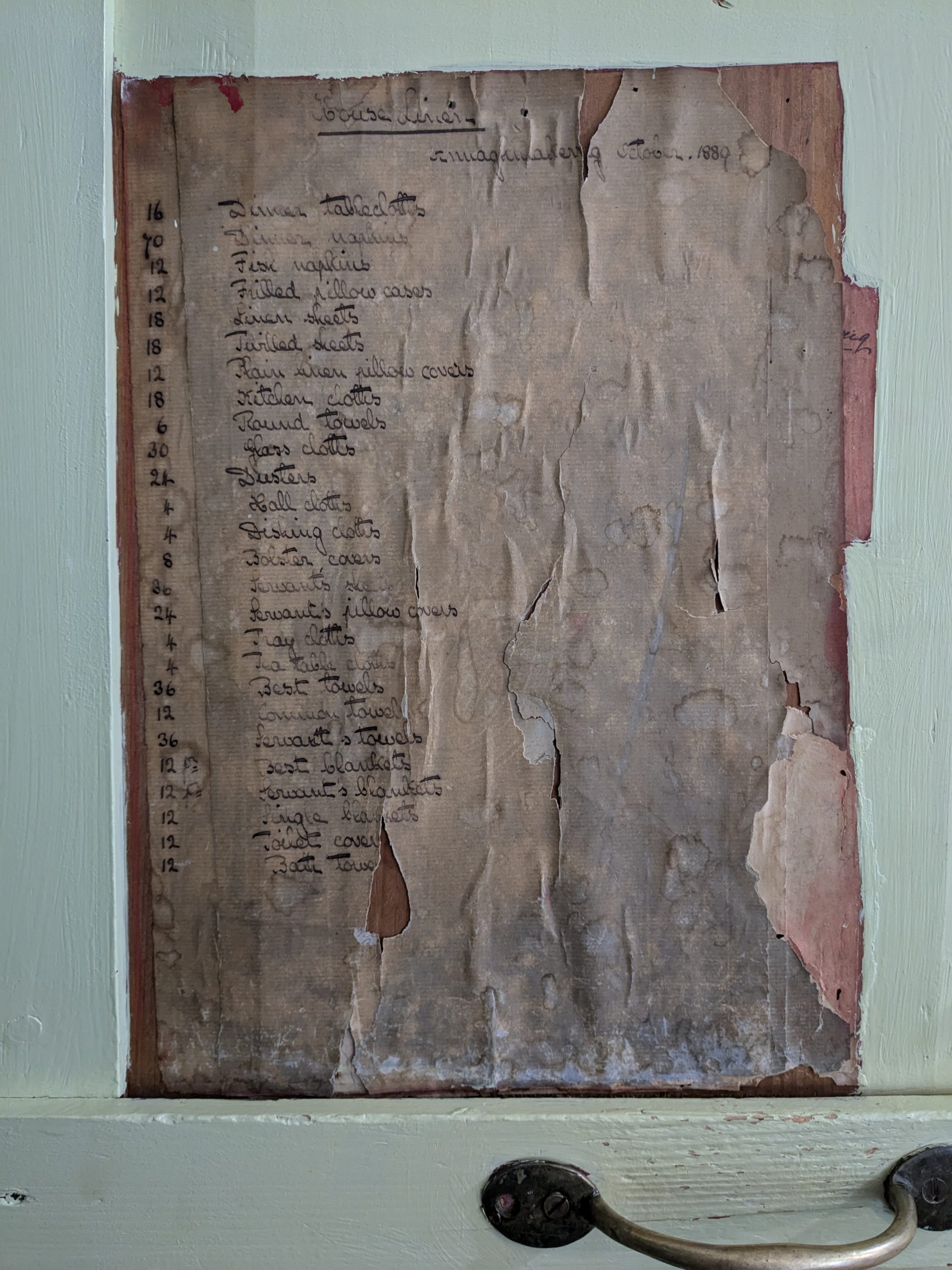

Because there’s really nowhere to go, apart from little walks in the forest, and nothing to do, gloriously, but work and think and talk with each other, we lavish the house with our attention. The hallways and rooms are full of art and artifacts. Every time I leave my room, I notice something new, or I pass another resident pulled up short in the hallway or the stairwell, examining something I’d missed. On the door to my bathroom, they have painted around a laundry list dated 1889. There are curious little insets and details everywhere in the walls. One night, someone convenes the few of us lingering at the table after dinner in the back hallway to look at a funny engraving hung above the fire extinguisher. We crowd in the narrow space and elect someone to read it aloud, squinting at the letters. The house has been changed only as much as strictly necessary, the soul not chased out of it by needless renovations. They have found a way to preserve it without trapping it in amber, a delicate balance achieved all too rarely, and so it still feels alive in a way I found almost spooky at first but have come to find comforting.

The Montreal triplex in my imagination feels very far away, but being here, in this big old country house built in the early years of the nineteenth century, kind of sharpens my perspective on it too. Many of the Irish artists here are facing the same tough housing situations as our communities back home. Where can people afford to live, how much of this precarity can be borne, how has it become so hard to live in the places we consider our homes?

So, my head feels full. Like it will take me some time after coming back home to digest all of this. In the meantime, this morning, I went down to the lake by myself. It had only just gotten light out and there was still a little mist hanging over the lake, and the water was completely still. I left my things by the boathouse and quickly walked straight in. It was freezing, it’s basically always freezing, but it was the first time I went in alone and the absolute quiet was so thrilling I stayed in a few moments longer than usual, till my hands and feet were aching. A little flock of birds came in low over the water and I could hear this strange sound, almost a hum, from the flapping of their wings. Fish were jumping to the surface, and scattering around my feet as I walked out and hurriedly dressed again before the cold set in too deeply, and then I came back up the hill and back up the beautiful staircase to return here to my desk for another day.

This blog post is part of QWF’s Dispatches from Ireland series written by the annual Max Margles Writer in Residence.